INTRODUCTION

This is the tenth and almost the last of the untold stories about the incredible moments of personal challenge and the decisions made that led to the 1989 side-by-side eight-hour battle between Dave Scott and Mark Allen. Everyone has seen accounts of the race itself.

Neither Dave nor Mark have told this story from each of their perspectives. But, more importantly, no one has ever heard the details of each of their personal journeys during the year leading up to The Greatest Race Ever Run.

In the previous nine stories Dave and Mark have revealed their personal struggles, their daily triumphs, and the seemingly impossible challenges that brought them to this iconic clash. Number 10 is about the actual race and you will definitely be surprised by parts of this story.

If you have been following our timeline of publication dates, you likely know that this one is coming to you one week late. You may be wondering why? In the end, what it took for both Dave and Mark to write these stories has been tremendous. Both have sunken back and experienced details both grand and painful that haven’t been fully felt by either of them for years.

This final story was the pinnacle of that experience for each of them. What it took for these two great athletes to write it was like how the Ironman unfolds in Kona. It takes just as much effort to close the final 10-miles of the marathon as the total amount of effort you have already put out in the previous 130.6 miles of racing to get to that point. Their effort epitomized that in writing the story of race day.

With that in mind, we also took extra time editing each of their incredible counts of a very personal experience so that hopefully you will feel every emotion and understand each detail as you read this very special story.

Many have written accounts of what happened between these two great icons on race day in the greatest race in Ironman history. This is the true story. This is what Dave Scott and Mark Allen were thinking and experiencing on this day. This explains why it was the greatest race ever!

After months of working together on these stories we all agreed that there was one more story to tell, so next week there will be the story about the making of the “story.” An epilogue if you will. It will be a story of changes in one relationship that has remained virtually unchanged for thirty years. It will be a story of courage in revealing a person’s darkest hours. Most of all it will be a story of the unreliability of perception, and of how telling our stories has the power to change perceptions into reality. We hope you’ll stay tuned for the unplanned final story of the 1989 Ironman. Look for it on Thursday, November 7th.

Scott Zagarino

Mark Allen

“You likely already know how this day ends. It was extraordinary in that both Dave Scott and I together forged performances and posted times that still have relevance today. This type of thing doesn’t just happen. A race that is timeless and drops the world record by close to eighteen-minutes can’t be predicted with numbers written in a training log and analyzed prior to the gun going off.

Yes, in hindsight you could argue that because of this workout and that time the potential was there for the results that are now history. But it’s the intangibles that can never be quantified that allowed this day to unfold as it did. I know most athletes want to have concrete data that explains everything, so as they make those leaps and bounds in their training they too can guarantee something amazing with take place in their races.

I’m not going to give you that kind of information in this final story, though—because it’s all the immeasurable elements of the performance and the completely illogical but clearly necessary decisions made in the heat of competition that enabled me to have the race I did on October 14, 1989.

I’ve had thirty-years to reflect on all those critical moments that happened in the 1989 IRONMAN, and I’m going to do my best in this story to explain them. They are the things that take us beyond the numbers. If you are interested in hearing the truth about my race on the day that became “The Greatest Race Ever Run”, then read on.”

Dave Scott

“Throughout the nine previous chapters in this series, leading up to race day—October 14, 1989—there have been historical moments and recollections brought back to me in reading Mark’s synopsis, talking to my friends and family, and delving into my memory bank regarding what truly transpired.

After writing each chapter, while proofreading, I would always need to add additional pieces to the “1989 Story.” These added memories quite often dripped back into the archives of my mind. My style in writing each chapter was to first jot down every thought or bullet point and then organize them in chronological order. This is likely a similar style for any author formulating a coherent and truthful document. However, nearly every chapter I wrote was laced with an additional seed I felt was pertinent and important.

Garnering my thoughts for Chapter 10, The Race, I realized my notes kept growing and growing, as small but significant elements of the race accumulated. I lettered all my bullet points and, as you will read, my list and the resulting paragraphs became rather lengthy!

Mark was always ahead of me in writing his chapters and maybe this was an appropriate manifestation of this project, given the race. The honesty of our chapters and the sharing of our individual stories was simply the truth. Given that Mark has been leading me in this “writing race,” I was able to read his version of Race Day before my version was complete. Reading his account was revealing and my first reaction was that he left out several key elements. The unfolding of the race actually began at the press conference the day before the gun went off.

So, I’ll begin my account of the race with a short prelude on one specific question that was asked by a reporter covering the event. All the top professionals were in the press room, including Mark, and I was asked, “Dave, what time do you think you’re capable of in tomorrow’s race?” I answered matter of factly and in a way that I assume my competitors thought was with a touch of arrogance. My response to the breakdown in splits was similar to what I stated in the ninth story. “I think 49 minutes-plus on the swim is doable, a 4-hour-35-minute bike and holding 6 minutes per mile ( 3’45”k) is my goal.” The reporter came back with, “Do you know what the sum is for these splits?” I didn’t respond but everyone in the room did the math and I’m sure Mark also took notice.”

Mark Allen

“For me, race day starts the moment I turn in my bike at the transition area late in the afternoon the day before the race. Once that is done, there is no more prep that can happen. Everything from that instant forward is about self-management. Manage the nerves. Manage the details like dinner and sleep and getting up on time and choking down enough calories by 5:30am to get me to my next feeding, which would be from the bottles on my bike early in the ride.

All other details are basic. Get up. Put sunscreen all over, well beyond your tan line because everything rides up on race day and if you don’t do that you’ll finish with a swath of painfully red skin in places normally unexposed to the sun. Grab the bag in the fridge with the bottles to put on my bike. There’s really no thought of the actual race. That’s already been mulled over a million times. Get in the car, in the back seat, and have my closest friends drive me the six miles, still in darkness, to the transition area at the pier.

That day, I said nothing during those miles. What was there to talk about? What could have been asked that would have had any effect? I was not a prize fighter who needed to get psyched up to weather physical blows to my body. I needed to do everything I could to get calm in the face of a day in which I knew I would ultimately not be the script writer. Rather, I would be the editor, taking the raw elements and hopefully crafting them into something memorable.

Those silent miles were both ominous and auspicious. It felt like a cross between going to your own execution and having a hint that you were being taken to your own surprise birthday party. The stark lights on the pier brought me back to what was going on. I was an hour away from my seventh IRONMAN in Hawaii. I had the same nerves as the previous six—but I also felt something new. I was excited to get the day going. “Excited” was never anything I had used in the past to describe that final hour before the race.

With a mass start, it was important to get at the front of the line of swimmers before the cannon sounded at 7:00am. All of us would go at once. There were both aggressive professionals as well as age-group athletes who were top swimmers willing to plow over anyone who got in their way. I hopped in the water about 6:45am. The sun was just coming up over the ridge of the crater next to the swim. It was beautiful. Brilliant. The water felt warm and soothing—and like home. For a brief moment the wonder and awe of Hawaii was all I heard or saw. Never before had I witnessed any of that. There was a peace inside me that was new.

Then I remembered my goal. Stick with Dave. I spotted him warming up off to the side of where most of the swimmers were. I backstroked over to him pretending like I didn’t see him. When I got near, I turned over, extended my hand and said, “Have a great race!”

Dave Scott

“Race day morning was similar to all my Ironman races: rise at 3:45 AM, have a small breakfast, go for a two-mile easy jog, take a warm shower and head to the pier. The easy run and shower were always a prerequisite for me in my previous six victories. The run was vital to enhance my circulation and to lightly stimulate my body before the short swim warm-up at the pier. This also had a quiet, calming effect during the dark early morning hours.

My close friends and family—Pat, Mike, John, Anna, and my sister, Jane—were in the condo all ready for race day. I sensed their anticipation of the race, with Pat crafting the locations of each person as the race unfolded.

After checking in at 5:45am, the nervous anticipation of the race felt a bit overwhelming. I felt the tension of the early morning and was eager to start the day. As in all my previous Ironman races, we could enter the water anywhere and at anytime. At 6:40 AM, I jumped off the pier slightly ahead of the starting line and swam out a couple hundred yards. Immediately, my nerves began to calm down Five minutes before the start, I took my normal position near the pier in what I thought was the best line to the turnaround boat. One-minute before the start, I was besieged by the other professionals who either decided they were going to follow me or make sure I was in close contact. Mark was close—very close—but I don’t recall exchanging words. I was merely aware of his presence.

When the gun sounded, I tried to hit my top speed within the first 15 meters. The Ironman swim was no different when it came to my intensity than an Olympic-distance race (1,500m versus 3,800m). My motive was to go out fast and see if I could break the swarm of athletes who surrounded me at the start.

The start was chaotic, with a lot of grappling, arms pushing down on my legs, slight body collisions, and a high level of frenetic posturing to garner the optimal drafting position. I realized that clear water was opening up and I could see the front swimmers breaking away from me. The gap between us was already nearly 25 meters, just within the first few minutes of the race—catching the leaders seemed improbable.

The draft position is critical and I had hoped to have a quick body in front of me. Having the sweet spot, directly behind an equal or slightly faster swimmer, was one of my ideal race scenarios. However, similar to all my IRONMAN swims, I was pulling the school of swimmers directly behind me.

I had commented to the media many times about the annoying foot tapping in previous races. So it came as no surprise to me when I felt multiple taps as we progressed to open water. The “tapping” is analogous to a slight bump when you’re running. For a brief moment, when this occurs there’s a dead spot in your rhythm. You have to restore your body and kicking alignment, plus maintaining a calmness about the irritating contact. Intuitively, I knew it was Mark bumping me, giving me a reminder of his presence. He had the golden spot directly behind me.

As the swim progressed, there were several times when my instincts told me to shake off, or at least shake up, the followers, including Mark. Without expending a massive amount of energy, I would accelerate for 100 to 150 meters and see if a gap would open. I tried this several times as the turn boat grew closer. Without knowing the potential string of swimmers that trailed me, my only concern was to put a physical and psychological dent into Mark’s psyche and to possibly drop him. At the turn-around boat, when I sighted the pier off in the distance, I gave one last surge to break away. Mark remained snug on my feet. My swim tactic now became to just maintain a steady effort to the completion of the swim. We exited the water together.”

Mark Allen

“BOOM! Chaos is the only way to describe the release of energy that happens in those first minutes of the swim. For a long time I had no idea where Dave was or who I was following. But as the day would have it, after about 500m I looked up and saw the feet I was following were attached to the guy whose signature swim stroke was as identifiable to me as his face. It was Dave Scott.

I respected Dave as an athlete and as a person. But I was also there to race and to exploit every advantage I could. I knew from comments he had made in the past that it irked him when someone hit his feet. So, why not? Every few minutes, caught in his draft, I accelerated slightly and give him a tap. Hello! I’m here!

By the end of the swim, well in front of us, and already out of the water, were two great swimmers: Wolfgang Dietrich and Rob Mackle. Dave and I finished the swim in the same position as we were shortly after the start. Dave led. I followed. And we came out of the swim-to-bike transition side-by-side. Both of us tried a new time-saving technique where we already had our cycling shoes clipped onto the pedals. The drill was to run fast, jump onto the bike, then slip your feet into your shoes while rolling. It quickly became clear neither of us had practiced it enough to get good at it. Literally 50m into the ride, as we both reached down to tighten the straps on our shoes, we crashed into each other and almost went to the ground. Yes, the great race of 1989 almost ended fifteen-seconds into the bike.”

Dave Scott

“My skill set in the transitions was historically shockingly slow and I wanted this one to be a bit more fluid. Coming out of the first transition, I was trying to flip my heel into my bike shoe. While weaving dramatically and trying to pay attention to my task, I somehow bumped Mark on his bike! I was grateful neither one of us went down, and thought this was quite a symbolic start to the cycling leg and the closeness of our next seven hours.

Heading up Palani Hill, which is about a kilometer in length, similar to the swim, I wanted to get on my pace right away. At the top of Palani, I heard that the leader, Wolfgang Dietrich, was one minute forty seconds ahead of me. In all IRONMAN races, I relished the leader position and my initial goal was to reel in Wolfgang. He was a world-class swimmer and a threat on the bike, and I certainly didn’t want him to increase his margin.

As I rode through the lava fields, my legs felt solid, fluid, and in control. I was keenly aware Mark was sitting behind me and Wolfgang was maintaining his lead. During that time, I thought it was just the three of us far ahead of anyone else. Nearly 15-years after the race, I was informed—and I also confirmed by checking the race-day splits—there was a swarm of athletes who exited the water with me and stayed behind me throughout the entire 112 miles (180km) of the bicycle leg. Kenny Glah, Mike Pigg, and Greg Welch were in this group.

Coming up to the 7-mile (12km) climb to Hawi, the turnaround point of the bike portion of the race, I upped the tempo to see if I could close the gap on Dietrich and, more importantly, squeeze Mark a bit more. The pace and discomfort was heightened but I reminded myself to be patient. There was no change as we made the turn. I barely caught a glimpse of Mark as we made the nearly 360-degree turn. He was within a few seconds of me. Wolfgang maintained his lead.”

Mark Allen

“For me there was only one person in the race—Dave Scott. Everyone else was background music in the elevator: you know it’s there, but you aren’t really listening. That was probably naïve, but it was my focus.

I shadowed Dave the entire ride staying just behind him. He knew how to pace the race. I didn’t. He was the best and I wanted to learn from him so that hopefully I could be my best. I had already tried being the flyer off the front on the bike and that had ended in disaster. No, this year had to be different.

Dave tried to get a read on how I was feeling a number of times. He’d look back. And the instant he did, I put my head down and looked off to the side. I didn’t want to give him the slightest clue as to whether I was strong or struggling. That seemed to suit him just fine. He went with his rhythms. It was clear a number of times he was trying to break me and everyone else who was following. I was happy to respond, and unwilling to set the pace. Like I said, he knew what he was doing. My goal was to try to figure out how to do this race right.

Normally I started to struggle when I got within about 35-miles of the finish of the bike. At that point, all the entertaining sections had passed, and it was just a grinding windy slog to get to the marathon. That’s when the reality of what I had gotten myself into always hit. But this year, I sailed through that transition from fantasy to the raw, unedited reality of the day without feeling any dip in how I felt. It seemed more like an adventure and a chess game than the IRONMAN. I was acutely aware of Dave, his pace, and how he was varying it. But I also found myself looking around at the Island. Mauna Kea was off to the left. It looked amazing.

We transitioned into the long, relentless slow-bake climbs out of Waikoloa through the newest lava on the course, which also meant it was the starkest. Instead of my usual feeling that this was racing hell, I couldn’t help but notice the amazing designs in the lava and the raw beauty of its vastness. This for sure was a shift for me. Peaceful. Feeling strong. Not worried. Just following the guy who knew how to throw it down.

After 2.4-miles of swimming and 112-miles of cycling, Dave Scott and I were still separated by no more than a few seconds. Amazingly, I still felt good and strong. Maybe my two 150-mile Wiggins rides were what it took for me to “normalize” 112-miles. The transition area where the bike ended was located 6-miles south of the finish line. Rolling through town to get to the transition gave you a preview of what was to come in the initial portion of the marathon—36-minutes of running with thousands of people cheering. This preview was like an alarm going off in the early morning when you are deep asleep. Riding through the deafening cheers of the crowd lining the road through town was a shock compared with what we had just completed: the long, lonely hours out on the Queen K Highway. But those closing miles of the ride also gave me more than enough time to contemplate all of what was coming: 26.2 miles of running.”

Dave Scott

“One of the race tactics I had mentioned to my “team” was to try a few long accelerations on the bike during the return home back to Kailua and the second transition. I had also anticipated Mark taking the lead or rolling up next to me on the back half of the bike leg. But on race day, he seemed content in shadowing me.

Reading your competitors body language, breathing rate, and pedaling cadence are key elements when it comes to recognizing fatigue. Because Mark never took the lead on the way home in the bike segment, I never had the opportunity to read him, and I had to singularly focus on what I could do since I could not rely on his tangible cues.

At mile 83 on the Queen K Highway, I tried my first acceleration for about ten minutes. This was not a noticeable attack, just a gradual increase in my intensity. My barometer of discomfort was intuitive and—without a power meter, heart rate monitor, speedometer, or wrist watch—my internal physiology was my guide. My legs felt great and I felt Mark would struggle a bit with this effort level.

But without looking back, I knew he was still maintaining my pace. I tried one more acceleration around mile 91. The added speed felt solid—but Mark once again responded by matching my tempo. Neither discouraged nor disheartened, I told myself we would start the marathon together and this was my strength.”

Mark Allen

“Dave Scott shot out of the final transition at a blistering pace, especially the way the course was designed back then. There was a short but intense climb out of transition that skyrocketed your heart rate even if you ran it easy. Then a long steady climb that lasted about 10-minutes, and then a short but brutal downhill. By the end of that your quads were toast and you were barely two miles into the marathon. Dave pushed it anyway. And I figured, he knew what he was doing, so I’d just stick with him. Our pace plummeted to around 5:50 miles. This was insanity at its best.

About halfway through our one-way stint through town someone bolted out of the crowd of thousands cheering us on. It was Dave’s wife, Anna. She held out their newborn son Ryan so that Dave could see him. And she didn’t just stand there. She started running alongside us. Yes, Anna with baby outstretched, was putting down a sub 6-minute mile!

My first thought was how can this woman holding a child be running a sub 6-minute mile? That was so amazingly impressive. But it was too much. I felt Dave’s energy surging. Seeing his son was like he got plugged into a nuclear power plant. This became the one and only time I spoke to Dave during the race. I said, “Hey, that’s not fair!”

Anna and Dave’s son dropped off, and Dave and I ran side-by-side, neither of us giving an inch or a second. The rest of the athletic world disappeared from my brain. There was only one thing to focus on, and that was Dave. We crested the infamous Palani Road hill and made the left turn back onto the Queen K Highway where we would run close to 20-miles. These were lonely miles as there were no longer crowds lining the course. In fact, the only people we saw were those at the aid stations every mile.

I felt tuned into Dave’s feelings without having to ask him. My energy was stronger than I had ever felt before. The lava that had intimidated me in all six previous IRONMAN races felt like a place I could surrender into and embrace. But at that point I was still in a “race” mindset—a “win or lose” framework. It was a mental place where, if I felt strong, I could keep going at full force. But it was also a place where, if I felt weak, I would default into the doubts and fears that had sunk my previous efforts.

As I ran shoulder to shoulder with Dave, I knew in my heart that my best race wasn’t going to come from “racing.” I had to find something beyond that. Unfortunately, mile after mile, that intangible remained hidden. Until…”

Dave Scott

“Speaking to my friend Mike over the past few months, we talked about his insight into the marathon. I mentioned that Mark had commented in a number of our interviews about 1989 that we couldn’t have had the record breaking day without each other. Mike’s comment was succinct and direct, and it actually paralleled my thoughts. “You don’t need Mark to race fast. He’s never been a contender at the end in any of your IRONMAN wins.”

I quickly reminded Mike that while it was true I had run fast without Mark, in 1984 and 1987 for example, but that Mark had been a factor. He had been ahead of me on the bike and well into the run in both of those races. I’d had to catch him and my goal had been to push myself to my limit. I’d hoped my pursuit would cause Mark to feel physically and psychologically vulnerable and inevitably falter with the pressure.

Mike replied, “You know how to win and you like to lead this race. Momentum is your gift. You can win number seven by outrunning anyone.” I felt the same way, but when the big day rolled around, I had company at the start of the marathon.

As Mark and I came out of the Kona surf side by side, I grabbed my shirt and set a blistering tempo—a tempo that was my pace. The initial hill coming from sea level is a nasty 11% pitch and it continues to climb at the top. But the pace had to be fast. Mark was not going to dictate the game on the run. I needed to be aggressive from the outset.

I caught Wolfgang quickly, before the second mile, and now the race was the twosome seemingly projected by the media and the history of our duels. Coming up to mile three, near the Sea Village Condo, one of the plans I’d discussed with my team was to have Anna bring Ryan out onto the run. Coming over a small undulating crest, I saw both of them—Anna had inched herself near the middle of the road and held Ryan in her arms. I felt magical!

My pace quickened, and Anna and Ryan gave me the biggest shot of adrenalin that temporarily erased the pressure of the run. Anna matched and held my running stride, with Mark a few steps behind us. The 5’48” mile (3’35” km) pace seemed effortless for Anna and myself! Mark within a breath of me, blurted out, “That’s not fair.” I thought he was joking, but in hindsight, I think he had a serious tone. No, it probably wasn’t fair, but for a couple minutes it was euphoria for me!

Quickly nearing mile three, the race was back on. During the first three miles, I’d had the inside position at the aid stations with an easy pass to my right enabling me to call out and grab my aid. Mark was on my left toward the middle of the street and it required him to drop back and grab his aid. He realized this and made a concerted effort to be on my inside—now the roles were reversed. Tactically, it was a crafty and cagey move. I was acutely aware I would now need to drop back 7-10 meters at each aid station and then surge back up. This was the race scenario as the miles clicked by. Bringing up this racing tactic is not a bitter pill nor is it an excuse for me. Mark’s timing and race savviness were spontaneous. I had to respond and I decided to drop back, surge up, and play this short cat-and-mouse game.”

Mark Allen

“By the half-marathon point Dave and I were not only the clear leaders, but also on pace to shatter his previous world record. We both wanted to be the person to do that. Neither of us was gaining any advantage to bring it into our court, though. That’s not to say no efforts were made, especially from Dave’s side.

He started surging, slowly but definitely. I barely hung on. He did it again. I maintained contact but struggled. He was clearly stronger on the downgrades, of which there were many. I felt a slight advantage on the upgrades. When it came to the flats, we seemed to be evenly paired.

Then it happened. We were closing in on the turnaround marker, which in 1989 was a gigantic 15-foot tall Bud Light inflatable beer can. You could see it for miles. It was like a mirage you could never reach.

But as it actually started to really look closer, Dave ratcheted up his pace. I was barely able to keep up. He held the pace. I thought, “This is impossible. I can’t hold this.” Suddenly, my mind went crazy with all the stuff that eroded my sense of confidence. “Dave’s too strong. He’s going to win. I can’t do it. It’s not worth keeping going. I just want to quit.”

Then it got so hard to match his pace I couldn’t even conjure up those negative thoughts. My mind went quiet as I tried to hold on for another few steps before throwing in the towel and surrendering to another stinging defeat in Kona. But in the instant my mind went quiet the most amazing thing happened.

Out of the corner of my eye, I thought I saw something. It was a revered 110-year-old Huichol shaman from Mexico that I had seen a picture of in a magazine in my condo two days earlier. His name was Don José Matsuwa. The photo of him smiling from cheek to cheek in the magazine had caught my attention. Don José had a look that was both peaceful and powerful. Those two qualities had been the essence of my how I always felt in the greatest races of my career. But I’d never felt either of those in the Kona.

In the moment I “saw” Don José in my peripheral vision sort of floating a few feet above the lava, I whipped my head to the side to look right at him. But when I did, the only thing I saw was lava. There was no Don José.

I turned to look straight ahead again. My mind went quiet once more. Dave held a 6-minute mile pace and exuded the most steadfast confidence I’d ever sensed in him. I didn’t know how long I could hold on before I cracked. But for some reason, I just stopped worrying about it. It was so much to match his pace that I couldn’t feel or think about anything other than keeping my focus on one step, then the next. The melodic pounding of feet on the pavement focused my mind on the silence that is always there when the mental chatter stops.

And there he was again—Don José, off to my right. But this time I didn’t look over. In that moment I felt something I can only describe as life force coming from him and filling my whole body with energy. A few moments later, Don José disappeared, but that energy kept building inside me, plugging me in and slowly charging me back up.”

Dave Scott

“Starting at the top of Palani Hill, the Queen K Highway began a relentless and long 8.5 miles (14.5km) to the Bud Light inflatable, which signified the turn back home at the 16-mile mark. The 1989 course went 1.5 miles beyond the airport turn, which truly was a mind-numbing stretch of endless lava fields. Coming home the final ten miles included the descent down Palani, a small loop back to the hot corner, and the finish on historic Ali’i Drive.

Nearing the airport, the turning point was visible. I realized on the return back for the final ten miles that I would have the inside position at the aid stations and Mark would be the one required to drop back. We made the turn at the Bud Light inflatable and there was a defining psychological moment that told me the race had just begun. Now is the time to confidently bring up the pace, I thought. Making the turn, Mark again made a strategic move to come on the inside close to the aid stations. I was temporarily caught off guard, but reminded myself as I brought the pace up that the race had approximately one more hour and my final move might need to be near the end.

Mark’s breathing, body language and his face, as I took a few quick glances at him striding beside me, were those of a masterful poker player. The signs of fatigue were subtle, a slight grimace, but neither of us showed nor allowed even a momentary glimmer of weakness. Mark was smooth with an effortless stride. My style was rough and unsightly, but my strength was the visual imprint I held internally. I floated and soared: effortless movement with each stride. This became my mantra and the final ten miles required the pinnacle of my concentration.

John, Mike, and Pat seemed to appear at different times over the miles. The massive throng of cyclists, mopeds, cars, and screaming fans seemed to grow exponentially as we neared Kailua. The noise, exhaust, and commotion heightened my senses that this race was coming down to the end.”

Mark Allen

“Don José was the first immeasurable moment of that day. Was the vision real? It didn’t really matter because like a dream you have at night that affects your next day, this vision transformed the race for me. Just as emotions like love and joy, equally immeasurable, can fuel amazing action, this vision brought me back into the race and gave me hope for something amazing to take place.

Less than a mile later the race hit a tipping point. From one foot strike to the next I went from struggling to knowing with every cell in my body that I could win the race. This was with 15-miles left to run. Never, ever before had I felt such a sureness in Kona.

But there was a problem. My quads screamed every time my feet came in contact with the ground. The pounding was intense. I had blood blisters on the arches of both my feet that were almost as wide as the arches themselves. They had both burst a mile earlier and the pain was searing each time my feet came in contact with hot pavement of the Queen K Highway. It was so intense I didn’t know if I could take another step. And then the real battle began.

“I know I can win. But I don’t know if I can keep going. I know I can win. But I just don’t know if I can take the pain and keep going.” Then the word that came to me in the little blue church before the race came back. It was the word I needed to have the race I’d come for:

“COURAGE”

I had to have the courage to keep going regardless of the pain or anything else that could hold me back. To do that, with Dave Scott still setting a body-breaking pace, I had to completely dissociate with the pain and stop thinking about the finish. There would be no matching his pace if I gave into the discomfort. There would be no victory if I didn’t take every step still left in the unfolding 15-miles.

I stopped thinking about everything, including Dave who I kept bumping into as we ran shoulder to shoulder. I thought nothing yet seemed to be aware of everything. It was like watching a movie of someone else’s life. The pain became background noise. Peaceful, yet powerful.

Dave was weakening ever so slightly on the upgrades. He’d then turn into a steamroller on the downgrades. It was getting difficult for me to keep up with him when we hit those stretches. I tried fading a half a step behind him on the uphills to hopefully throw him off and get him to think he was the stronger of us on them.

This was my eleventh day on the Island. Ten days earlier when I arrived as I drove from the airport into town, I had been calm enough to take in those critical eight miles of road where the marathon would be won or lost. And, for the first time in seven years, I saw how dramatic the final uphill was before the right turn and the steep downhill section of Palani Road that takes you to the final flat stretches to the finish line. As I saw this, I commented without even thinking, “This is where the race could be won this year, on this uphill.”

Dave Scott

“My buddies knew my final race tactic if Mark and I were still together. I heard Mike call out as we ran through mile mark 23. He was anticipating my move. As I dropped back to get a quick gulp of fluid replacement drink, I knew this would be my last needed aid. With a long climb that began very gradually at the bottom of Palani, I felt the fatigue of the race and closing the gap to get back to running side by side with Mark nearly took the entire mile. We were together again and I dictated the next move.

I heard a loud searing and screeching voice that resonated above the noise in which we were engulfed and realized it was Julie Moss (Mark’s future wife). She was perched on the media truck directly to the side of both of us. Looking up at the top of Palani Hill, I knew this was the moment I was going to break Mark. On the descent, I would sprint down the hill, hoping to lose him and not have a flat out race along Aliʻi Drive. My downhill running was reckless and fast, and my last and final decisive move to win the race neared.”

Mark Allen

“The uphill leading from the Queen K Highway to Palani Road came back to me as Dave and I continued to run stride for stride. “The race could be won on that uphill,” Now I knew why! It was the only piece of road demanding enough for a break to take place. The strategy became clear. Stick with Dave until the uphill. Grab one last glass of sport drink at the aid station that would be at the very beginning of that long upgrade, then go for it—and hopefully open up a gap big enough that he wouldn’t be able to catch me on the downhill into town.

The miles ticked by, one then the next. There was only one other person in my awareness, and he was keeping the pace as uncomfortable as possible without blowing up. Finally, I could see that aid station approaching. Dave accelerated just enough to get the inside track to the volunteers who had cups of precious liquid in their hands. I started to fall in behind. He grabbed for a drink. I started to reach out my hand as well when something yelled out at me, “GO!” I jerked my hand back and started sprinting. And in the few seconds it took for Dave to grab his sport drink, I’d opened up a gap of a few feet. It was the farthest we had been apart on the marathon—and the gap grew.”

Dave Scott

“Suddenly, Mark took off! I felt his surge at the bottom of Palani and realized my response had to be now—no waiting, no posturing, just simply matching Mark’s stride. For each stride, I could see a slight lengthening of the gap between us. Saying, “Go, go, go, Dave,” to myself my body struggled to hold form and to regain the margin. Mark pulled away and my body was tapped to the limit. The gap kept growing and growing.

There wouldn’t be an assault down Palani. I reached the top and heard, “33-seconds.” This was a gigantic and insurmountable lead. Mark was going to beat me and win his first IRONMAN. Running along Aliʻi Drive, with a deafening and cheering crowd, I felt honored but defeated.”

Mark Allen

“That voice that told me to sprint from the aid station was the second immeasurable moment that impacted the race. It was so counterintuitive. That late in the race, I was right on the edge of running out of gas. Every single calorie counted as far as keeping me going and preventing me from walking. Logic said I needed those final few calories. But wherever that voice came from, it knew otherwise. GO!

I got to the top of the hill before Dave. I could no longer hear his feet hitting the ground or his breathing, but I wasn’t about to look back to see where he was. I pushed the downhill on the other side as fast as I could without falling or having my legs cramp. But there was so much noise from people cheering that I couldn’t be sure if Dave was close or not. When I got to the bottom of the hill and was about to make the left turn onto the flat of Kuakini, I turned and took one look back up the hill.

I couldn’t see Dave, and in that instant, I knew I had done it.”

Dave Scott

“Anna and Ryan were at the finish line. Mark was engulfed by his family and friends. I stood there in shock and disbelief. I couldn’t respond and just wanted to hold my son. Exhilaration, sadness, and an overwhelming cascade of emotions swept over me. I had lost the IRONMAN to Mark Allen.

Reflecting on this race and pouring out my emotions and recollections has been a monumental journey. It took us nearly fifteen years before we actually shared our thoughts in a joint talk hosted by Bob Babbitt in 2004. This was the first time I had heard Mark’s voice describe some of the thoughts that permeated his account of the race. However, the story all of you have just read is real and raw, and it opened a vulnerable side to both of us.

When I look at Mark’s victory in this race, I simply say it was a race that brought out our best on one special day. Tactics, race plans, preparations with infinite detail—it was simply a riveting day of pure competition, gratification, and enjoyment. I hope all of you have relished Mark’s and my true story through the 1989 IRONMAN race.”

Mark Allen

“During those final closing minutes of running everything slowed. Time stretched, but in a good way. I floated on the emotion of my seven-year journey, knowing I was about to fulfill a dream that had tested me to the limit. For over eight hours I’d kept my emotions in check. But now I let them run free. With thousands of people cheering me on, I had my own smile from cheek to cheek and tears of joy that felt great to shed.

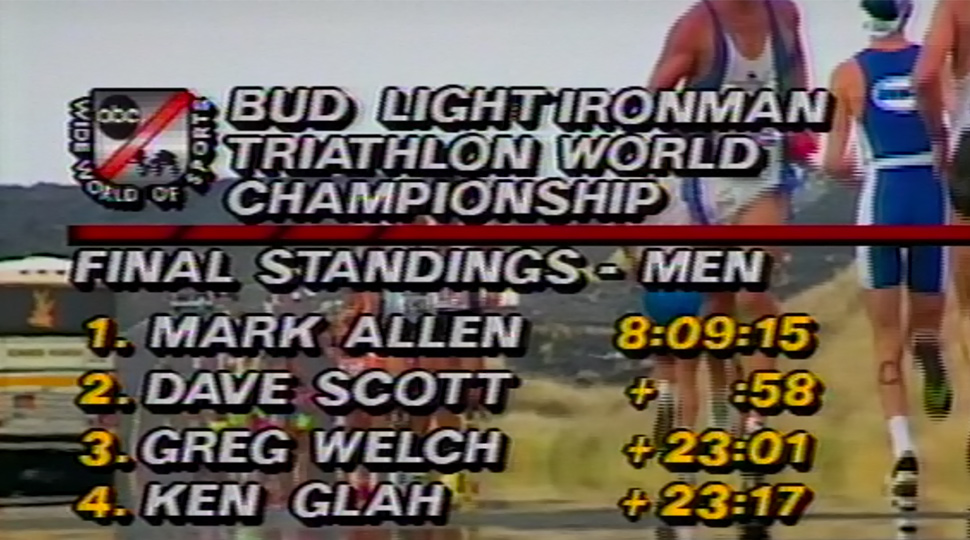

I finished in 8:09:15, which broke Dave Scott’s previous world record by about 18-minutes. Dave crossed the line in 8:10:13, a mere 58 seconds behind me. My marathon split of 2:40:04 stood for 27 years, one of the longest records in endurance sports history.

But the story of this race wasn’t me winning and Dave coming in second. The real measure of our battle is that it has stood the test of time and is still perhaps “The Greatest Race Ever Run”. Our race, waged between two long-time rivals, changed the way people viewed the IRONMAN. It was no longer a survival contest. It was now clear it could be a true race start to finish. Dave Scott had been racing it for years, but he had been in a race of one with himself before that day. The 1989 IRONMAN World Championship showed what truly is possible and what two athletes can create together.”