INTRODUCTION

This is the sixth of ten untold stories about the incredible moments of personal challenge and the decisions made that led to the 1989 side-by-side eight-hour battle between Dave Scott and Mark Allen. Everyone has seen accounts of the race itself. Neither Dave nor Mark have told this story from each of their perspectives. But, more importantly, no one has ever heard the details of each of their personal journeys during the year leading up to The Greatest Race Ever Run.

In the upcoming stories Dave and Mark will reveal their personal struggles, their daily triumphs, and the seemingly impossible challenges that brought them to this iconic clash.

Dave got himself on a roll as the hot days of August pressed on. Ever strategic, Dave plotted his route for victory and his body responded with flying colors. Meanwhile, Mark struggled. He’d overestimated the impact of racing the Olympic Distance World Championships in Avignon. A dramatic turn of events in late August nearly ended his quest for Kona. It was the second time their iconic matchup nearly evaporated into the thin air of personal choices.

A note to our readers. Some of the images accompanying these stories come from Mike Plant. Mike was one of the founding fathers of triathlon, and a voice for the sport from its earliest days. We lost Mike to cancer recently and in typical Mike Plant fashion he didn’t go without a fight. As this project is about legacy, it would not be right if he didn’t receive proper mention. We miss you.

Scott Zagarino

Mark Allen

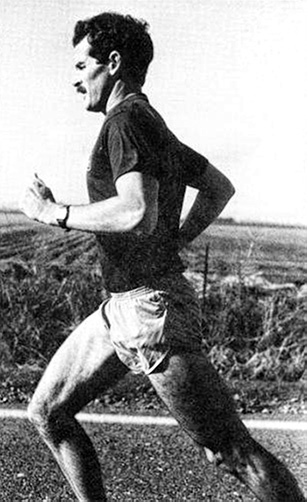

“By early August, 1989, on the outside it looked like I was on track to post an impressive race in Kona. I’d logged victories in every race I’d entered since the fall of 1988 including a Coors Light duathlon and the Music City Olympic Distance event after Avignon. The wins were coming at every distance, and by the time the “Streak” ended it would add up to 21 straight victories at every distance and discipline. The only thing missing from my playlist was a win in Kona. Yes, on the outside, I was flying high.

On the inside, I was struggling. What I really needed was a break to reset everything. All the training in New Zealand earlier that winter had been amazing, but it also took a lot of energy. All the training for the ITU World Championship had been intense, and I felt that I was resisting what would come in the next ten weeks getting ready for Kona.

But no break would come. There wasn’t time.”

Dave Scott

“One week into my “comeback” post-Ryan’s birth, six weeks to go before the race, my close friend Mike and I were back playing our game of cat and mouse. Mike had told me to sign up for my first IRONMAN World Championships in 1980—he had recognized my insatiable appetite and skill in all three disciplines—and since then we had developed an uncanny training pattern that enriched both of us.

Mike and I had completed over 300 workouts that always ended up in a calculated time gap between the two of us. He was a solid runner and initially pushed me on our runs, but he dramatically lagged behind on the bike and swim sessions. But allowing a time gap between us or having Mike turn home early allowed me to pursue him, and that relentless chase became our individual motivators. My quest to catch Mike released a hidden energy that allowed me to quietly race anyone—even Mark Allen.

Mike and I created both spontaneous moments and pre-programmed training efforts that became my maniacal quest to always try to catch Mike. We might race a sprint mile on the end of a run or for the final 25 yards of a swim session.

But when I reflect back on these sessions only weeks before Kona, and the race scenarios that always percolated through my mind, every session with Mike became a race on the Ironman course.

One particular August day, our first workout was on the bike. I rode for around five hours. In our pre-ride choreography meeting, we had decided to ride to a predetermined landmark where Mike would turn back but I would continue further down the road, knowing our race was just beginning. My ride would total approximately 102 miles, while Mike’s ride equalled 93. As a result, he had a twenty-minute lead at the point that he turned.

My goal was to time trial the entire distance after he turned and hopefully catch him inside of three miles from the finish. There were days on that straight, farm road outside of Davis that I would catch him in the final 200 meters. Mike and I had played this game over and over since 1978 and had repeated it in preparation for all of my IRONMAN races.

My secret motivator that drove these competitions had nothing to do with Mike, though. Inside, I envisioned myself either pulling away from Mark—or catching Mark and then screaming by him.”

Mark Allen

“Fatigue and willpower often battle for supremacy in the same place. I needed something to anchor my resolve in to keep going even though I felt tired and wanted to back off my training. But finding that anchor was difficult. Every positive moment when I said “Okay, I need to train” got shot down by the unknown of Dave Scott. I had been building him up in my mind to be this invincible bigger-than-life presence that I actually knew little about.

I didn’t know how he trained other than vague stories I had heard about how he would punish himself with insanely hard workouts. Without knowing what those sessions were, it was easy for me to let them take on mythical proportions in my mind’s eye. I imagined him out there sweating up a storm, pushing beyond the limits of human tolerance, with a steely will that never wavered.

Of course, that was probably not the case. But the more I struggled to find a hook to bring me back up to the surface and get me back to training, the myth of the unknown of Dave Scott grew into an overwhelming, unstoppable presence.

Fortunately, my training partners helped pull me out of the never-ending spiral of questioning whether Kona was worth going for one more time. One of these training partners in particular was Ken Souza. He was the top duathlete (run/bike/run) in the world. Ken looked like John Bon Jovi in lycra, with hair down past his shoulders.

He was about as non-analytical as you could get when it came to finding motivation. “You just go out there and kick ass. You do it in training; you do it in the races. Don’t even think about it for one second because that shit will destroy you.”

That was Ken’s way of getting things done. Those weren’t his exact words, but for sure it’s how he approached everything we did together in training. And his attitude was infectious. He didn’t even open up a space for backing off to take hold. It was full throttle, don’t look back, and hope you got to the finish before you crashed.

Ken also knew what peak athletic performance took—which was training designed to push every gene in your body to the limits. And he knew the only thing on my mind was Kona. So, he came up with something we would do together that he thought was going to be one of those epic sessions to completely reset the bar on a key piece of Ironman: how to have a fast bike that didn’t actually exhaust you.

He told me he looked at a map and there was a town called Wiggins exactly 75 miles due east of Boulder, Colorado, where we lived. He said there was a gas station in Wiggins that we’d turn around at. So, it would be an out and back ride of 150 miles.

“We’ll go so far east that we won’t even be able to see the Rocky Mountains anymore,” he said. I guess he thought that statement was supposed to be inspiring. It was, but in a big, hairy, set-a-new-standard kind of way.”

Dave Scott

“I knew Mark had his own valued training partners and he was relishing the same type of success. But could he punish himself enough without someone like me right next to him? I had my doubts, but there was also never a moment to feel overly confident. Mark had won every major race under all types of conditions and against all types of athletes, but I had to disregard these victories and recognize the one elusive goal of his—Kona.

Confidence is a strange concept and, as I’ve mentioned, I was always able to peel back the layers of doubt and bring up my mental game prior to the World Championships. There seemed to be an illusion I could just push a button and ignite the most ferocious flame and be ready to have a magical race. The press always built up my aura as this mystical, self-driven, highly motivated guy who didn’t need extrinsic motivation to excel.

I knew this wasn’t true. I was not a hermit. I had numerous friends from my home town and always thought I was a well balanced guy. The media painted me as a man of solitude and somewhat of an outcast. But rather than fight that stigma, I worked it in my favor. My competitors had developed a fear of this fabricated “Dave Scott” myth. I would use this same false identity heading to Kona in October. Without the intimate knowledge of why Mark faltered in his previous five Ironman races, I wanted to sow every seed I could to create doubt in his mind.

On that training ride in August, Mark was on my mind: Mike became “Mark” and my goal was to catch him. I knew Mark was mentally a master in all of his races. Defeating Mark would require not only a supreme race day, but also reaching a mental and physical breaking point where he finally would concede. My training days required me to develop and confirm my own internal drive to reach that breaking point.

Zeroing in Mike was now my immediate goal. That day, Mike turned home and I carried on to the predetermined turnaround point. On the return home, we had to climb over Cardiac Hill, approximately a two-mile climb with a hearty pitch at the top. By my calculation, Mike could lose four minutes to me just on the climb. After that, our race would be to hold each other off over the final forty miles home.

Finally with just six miles to our finish point, I saw Mike. The margin between us was still over a mile. Mike was not truly in my sights, but I pressed on. I caught him just 1.5 miles from the finish—a decisive victory for me considering the history of our training competitions—and from there we rode in the final distance together.

Finishing this duel with Mike was a statement that I was becoming ready. Mike’s time was consumed with his work as a physician, his finishing time in Kona was over ten hours, and in the grand scheme of things he was hardly a formidable foe. But when the stakes were set and pride was involved, both of us had an uncanny desire to beat each other—a desire that resulted in excellent training. Mike was my barometer to measure my workouts and hopefully transcend these sessions with my seventh victory in Kona that October.”

Mark Allen

“Ken and I’d had no idea what lay between Boulder and Wiggins other than a lot of pretty flat farmland. It was completely unknown if there would be stores or gas stations along the way to get water and more fuel. But nevertheless—Wiggins it was! That was the anchor I needed to get my brain back into the one goal I had for Ironman, which was to have the best race I could possibly have. That ride would certainly do something for my fitness I’d never had before. That was inspiring. And just that thought seemed to erase my feeling of being tired. It silenced any doubts I had about whether the next ten weeks would be worthwhile or not.

The plan was to do the Wiggins ride in two weeks time to give me a chance to regroup and recharge after just getting home from Avignon and the World Championships. I went about my basic rebuilding training, which was lower intensity and nothing extreme on the endurance scale. It wasn’t a real break, but I thought I was backing off enough that I could refill my depleted reserves without compromising fitness. With Kona so close, though, it would be easy to ignore the small signals that my training was too much. Those kinds of signals got squelched with the bigger voice of the Ironman coming in October speaking.”

Dave Scott

“The truth of how I felt was quite the opposite of everything the media portrayed. I struggled.

Despite driving myself relentlessly and having my ongoing training battles with Mike, I feared the fact that the World Championships were less than six weeks away. My fear was perfection. And in that fear of perfection, my fears of success and failure were intertwined. The problem with walking a fine precipice of either being successful or failing was that the margin of error was very narrow. If I strove for success at the level I chose, failure inevitably loomed, and that caused me to fear both.

I wrestled with both those fears throughout my life—if the standard of perfection I set for myself was not achieved then I failed.

As a result, I seemed to emotionally flutter after my successes and slip back into a pattern of failure.

My success was never good enough.

I was haunted by these fears. Did I need Mark to push me or could I mentally rally and go into the race with a supreme confidence that radiated from my preparation? Again, my anxiety swelled with the idea of accepting the results and nurturing the positive. To be perfect always created a level of angst and uneasiness that continually needed squelching. But I knew my remaining training sessions had to be completed with fulfillment and gratification. These feelings would only heighten my potential for the race.

Mike and I continued to train together, primarily on the weekends. I tried to adjust to a new level of sleep deprivation with my son waking several times each night, but whether I adjusted or not there would be no more breaks until race day.

The training clock was moving fast.”

Mark Allen

“A week after returning from France, I went to the Masters swim workout I always attended. Ironically, it was coached by Dave Scott’s sister Jane. It was the one place Dave and I had crossed paths in the past. Jane explained the workout and the main set we would be doing that day. Right before the set started, I hopped out of the pool to go to the bathroom. I figured better to go then than have to exit in the middle of the workout.

The men’s bathroom was a typical men’s locker room with toilets and urinals. My needs involved the simpler of those two options. I stood there untying my suit when the whole world went dark. My focus changed from normal to a pinpoint in a second. The whole concept of vision was gone. Awareness of where I was completely shut off. I disappeared into zero consciousness.

At the instant I came back to seeing and became aware of where I was,

I found myself falling at an uncontrollable speed toward the porcelain of the urinal. My head slammed into the top of it just above my eyebrow with a force I thought would surely split the skin on my forehead. I’d blacked out and then came to just as I was collapsing to the ground. I couldn’t hold my body weight and crumpled to the floor of the bathroom.

There on the floor, the questions spun through my head. What had just happened? Was I okay? Why was I even there at the pool? My world expanded and shrunk at the same time. What was really important? Was trashing my body to the point of collapsing in the locker room worth it? Why would I ever even want to find a reason to keep pushing my body to the limit day after day if this was the result? Even the thought of that as I lay there on the floor felt like some kind of sick obsession.

And the answer I came up with?

There was nothing about a victory that was worth risking my physical health. Life just slapped me in the face with a blow to my head on a cold, hard urinal. Something was telling me to wake up and see the dramatic cost the training was demanding from my body.

I sat there on the floor for quite a while. How much time I don’t know for sure. Enough had pasted though that when I eventually went back out to the pool deck everyone started harassing me for missing most of the main set. “Now you come back out? The set is almost over!” They had no idea what had just happened to me. I had a small cut and a big lump on my forehead, but I was able to hide it by pulling my swim cap forward and over the wound.

I got back in the pool to finish the workout I had started. But I was not going to go back to my scheduled Ironman training. My motivation to even do another day in the sport had been knocked out of me when my head came in contact with a surface that had zero give.

I was done. Not only was the Ironman in October done. My career was done.

As I lay in bed that night, there was not a single reason in the world I could come up with good enough to change my mind. There would be no way to explain to the sports world how whacking my head on a urinal with nothing other than a lump to show for it was the reason I was going to retire from the sport. But to me it made total sense.

It was like an experience of dying. “I” was no longer an entity with consciousness. “I” was obliterated and gone. But the “I” who was still alive wanted to go on and have a good life. And if there was something about what I was doing in the sport that was compromising my chances of a long and healthy life, then it was time to say goodbye to triathlons.”